I. Unveiling the Mystery of the Zeigarnik Effect

Have you ever had experiences like these? When watching a TV drama, just as the plot reaches a thrilling part, an advertisement suddenly comes on. Even though you detest the advertisement, you can’t help but watch it through for fear of missing the subsequent plot. At work, when you haven’t finished the task at hand but have to deal with other things, your mind is full of the unfinished work, and you can’t concentrate on the new task. In fact, there is an interesting psychological phenomenon behind these – the Zeigarnik Effect.

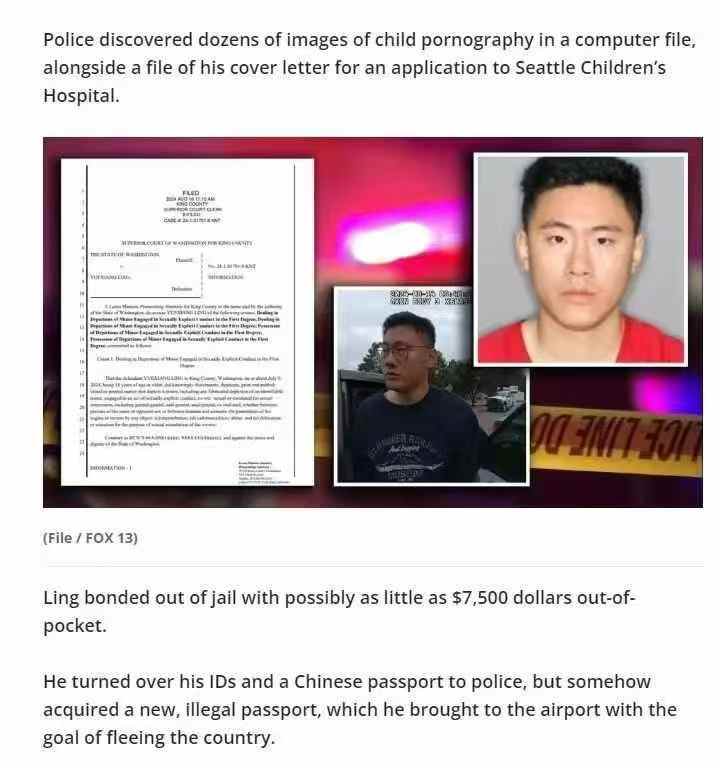

The Zeigarnik Effect originated from a memory experiment conducted by the German psychologist Β.Β. Zeigarnik in the 1920s. She had the subjects perform 22 simple tasks, such as writing a favorite poem, counting backwards from 55 to 17, etc. These tasks took approximately the same amount of time. During the experiment, half of the tasks were allowed to be completed, while the other half were interrupted before completion, and the order of the completed and uncompleted tasks was randomly arranged. After the experiment, without any prior notice, the subjects were asked to recall the 22 tasks they had done. The results were astonishing: on average, 68% of the uncompleted tasks could be recalled, while only 43% of the completed tasks could be remembered. This shows that people have a deeper memory of uncompleted tasks.

Why does this phenomenon occur? From the perspective of the brain’s working mechanism, when we start a task, the brain allocates attention and cognitive resources to it and enters a state of “psychological tension.” As long as the task remains unfinished, this state of tension persists, constantly reminding us to complete it, thus keeping the relevant information highly active in our memory. When the task is completed, the brain deems the matter resolved, the sense of tension is relieved, and the attention and memory intensity towards it gradually decrease.

This effect can be seen everywhere in life. For example, when you are reading a fascinating novel and suddenly have to put it down due to something, even when doing other things later, the plot of the novel often pops up in your mind, and you keep thinking about the fate of the protagonist. Or, when chatting with a friend and the other person’s words are interrupted halfway, you may keep wondering about what they didn’t finish saying.

II. Skillfully Using the Zeigarnik Effect to Initiate an Efficiency Revolution

Since the Zeigarnik Effect holds such a powerful force, how can we skillfully apply it in our work to boost our work efficiency? Don’t worry. Next, I will introduce three key steps in detail.

Step 1: Task Decomposition, Creating a “Sense of Incompletion”

When faced with a huge and complex work task, do you feel at a loss and overwhelmed by pressure? At this time, task decomposition becomes your “secret weapon.” Breaking down a large task into smaller tasks is like dividing a mountain into steps. With each small task completed, you get one step closer to the mountaintop.

Take writing a project report as an example. This is no easy task. If you think about completing a full – fledged report right from the start, you may find it extremely difficult and not know where to begin. However, we can break it down into several small tasks: determining the topic, collecting data, organizing data, writing an outline, filling in the content, and proofreading and reviewing.

When you start to determine the topic, your mind will keep thinking about it. Because the topic has not been finalized yet, this “sense of incompletion” will drive you to keep exploring, striving to find the most appropriate and appealing topic. After finalizing the topic and moving on to the data – collection stage, you will find that there is a large amount of information to be dug up. Every time you find a valuable piece of data, you will realize that there is still more data to be collected. This “sense of incompletion” will keep you highly focused and motivated, constantly expanding the sources of data and enriching its content.

Through such task decomposition, each small task comes with its own “sense of incompletion,” motivating you to complete it as soon as possible, thus facilitating the smooth progress of the entire project report.

Step 2: Reasonable Interruption, Strengthening Task Memory

Interrupting tasks at the right time is also an art in the work process. A reasonable interruption not only won’t affect work efficiency but can also deepen your impression of the uncompleted part, allowing you to regain your working state more quickly when you resume work.

Suppose you are designing a poster. You have completed the overall layout and the design of some elements, but you encounter a creative bottleneck when dealing with the key visual elements. At this point, you can choose to temporarily interrupt this task and do something else that is relaxing, such as having a cup of coffee, stretching your body, or chatting with colleagues.

When you interrupt the task, although your body is engaged in other activities, your brain doesn’t completely stop thinking about the poster design. Subconsciously, it keeps pondering the uncompleted parts, sorting out and optimizing the previous ideas. When you return to the poster – design work, you will be pleasantly surprised to find that the problem that troubled you before may have a new solution, or you can re – examine the design from a new perspective and complete the subsequent work more efficiently.

However, pay attention to the timing and duration of the interruption. The interruption should be timed at a key point of the task, such as when an important module is completed or when you encounter an obstacle that is difficult to overcome. The interruption duration should not be too long to avoid forgetting task details and ideas. Generally, 15 – 30 minutes is more appropriate.

Step 3: Setting Goals, Creating “Incompletion Tension”

Clear goals are like lighthouses in the dark, guiding us forward. Under the influence of the Zeigarnik Effect, goals can also generate a kind of “incompletion tension” that drives us to keep moving towards them.

Take sales work as an example. We can establish a phased goal system. For example, within a month, divide the goals into weekly and daily goals. In the first week, set the goal of developing 20 new customers. Within this week, further break it down to developing at least 4 new customers per day. When you strive towards this goal every day, you will find that as long as you haven’t reached the daily goal of 4 new customers, there will be a sense of nervousness and urgency in your heart. This feeling is the “incompletion tension.” It will prompt you to keep looking for potential customers, optimize your sales pitch, and improve your sales efficiency to complete the goal as soon as possible.

When you complete the daily goal, you will immediately focus on the next goal because the monthly sales goal has not been achieved yet, and a new “incompletion tension” will arise, motivating you to keep working hard. Through such progressive goal – setting, you can keep yourself in an active working state and fully utilize the motivation brought by the Zeigarnik Effect.

III. Flexible Application for Continuous Improvement of Work Efficiency

Through the three steps of task decomposition, reasonable interruption, and goal – setting, we can skillfully utilize the Zeigarnik Effect and transform it into a powerful driving force for improving work efficiency. In actual work, you may flexibly apply these methods according to your own work characteristics and habits. At the same time, pay attention to observation and summary to see which method suits you best and which aspects need further adjustment and optimization. I believe that as long as you keep trying and improving, you will surely be able to give full play to the advantages of the Zeigarnik Effect and take your work efficiency to a new level.