Introduction

The bystander effect, a phenomenon deeply ingrained in social psychology, has far – reaching implications for our behavior in emergency situations. It refers to the tendency that the greater the number of bystanders present during an emergency, the less likely any one individual is to intervene. This counter – intuitive behavior has puzzled researchers and the public alike for decades.

In this article, we are about to uncover 10 shocking facts about the bystander effect. These facts will not only reveal the extent of this phenomenon but also delve into the underlying reasons why a staggering 90% of people often fail to act when others are in need. By understanding these facts, we can gain valuable insights into human nature and social dynamics, and perhaps, find ways to encourage more people to be the heroes in times of crisis.

Fact 1: The Kitty Genovese Case

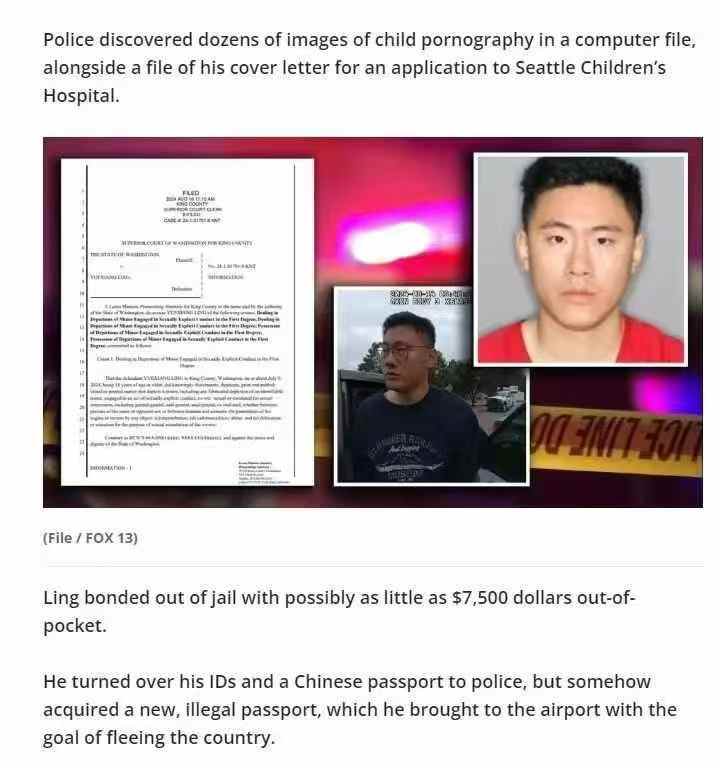

The murder of Kitty Genovese in 1964 is the most iconic example that brought the bystander effect into the spotlight.

On the early morning of March 13, 1964, 28 – year – old Kitty Genovese was returning home to her apartment in Queens, New York. As she was approaching her building, a man named Winston Moseley attacked her. The attack was brutal and lasted for approximately 30 minutes. During this time, Genovese repeatedly cried out for help, yelling, “Oh, my God! He stabbed me! Please help me!”

The terrifying incident unfolded in plain sight of her neighbors. Reports initially stated that as many as 38 people witnessed the attack from their windows but failed to intervene or even call the police in a timely manner. Some watched from the safety of their homes for an extended period, while others simply closed their curtains, choosing to ignore the desperate cries for help.

It was only after the attacker had fled for the second time that a neighbor finally called the police, but by then, it was too late. Genovese succumbed to her injuries on the way to the hospital.

This tragic event shocked the nation and led to widespread public outcry. It also prompted psychologists Bibb Latané and John Darley to conduct in – depth research on the phenomenon that became known as the bystander effect. Their studies aimed to understand why so many people would stand by and do nothing while someone was in mortal danger. The Kitty Genovese case became a catalyst for a new era of research into human behavior in emergency situations, highlighting the complex social and psychological factors that can prevent individuals from taking action.

Fact 2: The Diffusion of Responsibility

One of the primary psychological mechanisms behind the bystander effect is the diffusion of responsibility. When an emergency occurs and there are multiple bystanders present, individuals tend to feel that the responsibility to act is shared among the group. As a result, each person’s sense of personal responsibility is diluted.

In a classic experiment conducted by Bibb Latané and John Darley, participants were placed in different situations. In one scenario, participants were in a room alone when they heard someone in distress. In another, they were in a room with several other people when the same distress signal was heard. The results were striking. When alone, a large majority of participants quickly took action to help the person in need. However, when in a group, the likelihood of any one individual intervening dropped significantly.

Participants in the group setting often thought, “Someone else will surely do something.” They assumed that because there were more people around, the responsibility to act was no longer solely on their shoulders. This diffusion of responsibility can be so powerful that it can lead to inaction even when the situation is clearly an emergency. For instance, imagine a person fainting on a crowded subway platform. With so many passengers around, each individual might assume that another passenger is more qualified or more likely to call for help, leading to a collective failure to act in a timely manner.

Fact 3: Social Influence and Conformity

Social influence and conformity play a significant role in the bystander effect. People have an inherent tendency to look to others for cues on how to behave, especially in ambiguous situations. When faced with an emergency, if those around them are not reacting, individuals are likely to follow suit.

In a study, researchers staged an emergency situation in a room filled with actors. When the actors showed no signs of concern or intention to help, the real participants were much less likely to intervene. They were influenced by the non – responsive behavior of the group, believing that if no one else was acting, then perhaps the situation wasn’t as serious as it seemed.

Another example could be a car accident on a busy street. If the first few passers – by simply glance at the accident and keep walking, subsequent bystanders may be more likely to do the same. They conform to the behavior of the initial group, assuming that their lack of action is a sign that intervention isn’t necessary. This conformist behavior can quickly spread, resulting in a large number of people passing by the emergency without taking any steps to assist.

Fact 4: The Role of Pluralistic Ignorance

Pluralistic ignorance is another crucial factor contributing to the bystander effect. It occurs when individuals in a group privately believe one thing but assume that everyone else in the group believes the opposite. In the context of an emergency, this can lead to a situation where everyone is actually concerned about the situation but fails to act because they misinterpret the non – action of others as a sign that there is no cause for alarm.

Consider a situation where a person is lying on the ground in a public park, seemingly unconscious. The bystanders might each be worried about the person’s well – being, but when they look around and see that no one else is making a move to help, they assume that the others know something they don’t. They might think that perhaps the person is just taking a nap or that there is a non – emergency reason for their position. Each bystander is waiting for someone else to take the first step, based on the false assumption that the lack of action from others indicates that action is not required.

In a research study, students were placed in a room where smoke started seeping in through a vent. When alone, most students quickly reported the potential danger. However, when in a group, and the other “bystanders” (who were actually actors) showed no reaction, the real students were much less likely to report the smoke. They privately thought the situation was dangerous but assumed that the non – reaction of the group meant it was not a serious issue, thus falling victim to pluralistic ignorance. This misjudgment of others’ attitudes can prevent people from taking action in an emergency, even when they might otherwise be inclined to help.

Fact 5: The Impact of Group Size

The size of the group of bystanders has a profound impact on the likelihood of intervention. Research has consistently shown that as the number of bystanders increases, the probability of any one individual offering help decreases significantly.

A study conducted in a laboratory setting simulated an emergency situation. When participants were in a small group of two or three people, the rate of intervention was relatively high. However, as the group size grew to six or more people, the likelihood of someone stepping forward to assist dropped by nearly 50%. This decrease in helping behavior can be attributed to the diffusion of responsibility and social influence. In larger groups, individuals feel less accountable for their actions and are more likely to conform to the inaction of others.

In real – world scenarios, this phenomenon is also evident. For example, on a busy street corner in a large city, if a person suddenly collapses, with dozens of people walking by, the chances of immediate help are slim. Each passer – by may assume that someone else will call for medical assistance or perform first aid. The large number of bystanders creates a sense of anonymity and a diffusion of the responsibility to act, leading to a collective failure to respond promptly.

Fact 6: The Fear of Evaluation

The fear of being evaluated by others is a powerful inhibitor of action during emergencies. People often worry about how their behavior will be perceived, judged, or criticized by those around them. This concern can be so overwhelming that it leads to inaction, even when someone’s well – being is at stake.

In an experiment, a situation was staged where a person was clearly in need of medical assistance in a public area. Some bystanders were made to believe that their actions were being closely observed by others. As a result, those who were under the impression of being watched were much less likely to offer help. They were afraid that if they made a wrong move, like performing first aid incorrectly, they would be judged negatively.

Another example can be seen in a scenario where a person is verbally harassed on a crowded street. Bystanders might be reluctant to step in because they fear being seen as meddling or making the situation worse. They worry that their attempt to intervene could be met with scorn from the harasser or even from other onlookers. This fear of social evaluation can create a sense of self – consciousness that paralyzes people, preventing them from taking the initiative to help.

Fact 7: The Ambiguity of the Situation

The ambiguity of an emergency situation can significantly impede people’s ability to recognize it as such and take appropriate action. When the nature of a situation is unclear, individuals often struggle to determine whether it truly requires their intervention.

For example, imagine a person sitting on a park bench, looking a bit disoriented. Passers – by might not be sure if the person is simply tired, has had too much to drink, or is experiencing a serious medical issue like a stroke or hypoglycemia. In such a case, the lack of clear signs of distress makes it difficult for bystanders to make a decision. Some may think, “Well, maybe they’re just having a bad day and need some space,” while others might be hesitant to approach due to the uncertainty.

In a study, researchers set up a situation where a man was lying on the ground outside a building. Sometimes, he was clearly in pain and calling for help, and in other instances, his behavior was more ambiguous. When the situation was clear – cut, a large number of people stopped to help. However, when the situation was ambiguous, the number of people who intervened dropped drastically. People tend to rely on clear cues to identify an emergency, and in their absence, they are more likely to err on the side of inaction, afraid of misinterpreting the situation and embarrassing themselves or causing unnecessary trouble.

Fact 8: Cultural Differences in the Bystander Effect

Cultural differences play a significant role in the manifestation of the bystander effect. Different cultures have distinct values, norms, and social expectations that can either amplify or mitigate the likelihood of bystander intervention.

In individualistic cultures, such as those in the United States and Western Europe, the focus is often on personal achievement, independence, and self – reliance. In these cultures, the bystander effect may be more pronounced. People may be more concerned with their own image and the potential negative consequences of getting involved in someone else’s affairs. For example, in a big American city like New York, a passer – by might be hesitant to help a person in need on the street, fearing that they could be blamed if something goes wrong or that it could disrupt their own busy schedule.

On the other hand, collectivist cultures, like those in many Asian countries such as Japan, China, and Korea, place a greater emphasis on group harmony, loyalty, and the well – being of the community. In these cultures, the bystander effect may be less prevalent. People are more likely to feel a sense of collective responsibility and are more attuned to the needs of others within their social group. For instance, in a small Japanese town, neighbors are more likely to come to the aid of someone in an emergency because they see themselves as part of a close – knit community where everyone looks out for one another.

Cross – cultural studies have also shown that cultures with strong norms of prosocial behavior, such as helping others without expecting anything in return, are more likely to have higher rates of bystander intervention. In contrast, cultures where there is a greater sense of mistrust or where self – preservation is highly valued may experience a more significant bystander effect. These cultural differences highlight the importance of understanding the social and cultural context when analyzing why people do or do not act in emergency situations.

Fact 9: The Bystander Effect in the Digital Age

In the digital age, the bystander effect has taken on new and concerning forms. With the prevalence of social media and online platforms, incidents of cyberbullying and online harassment have become alarmingly common, and the role of bystanders in these situations is a cause for great concern.

When a person is being targeted by cyberbullies, a large number of online viewers may witness the abuse. However, just like in real – life emergencies, many of these online bystanders fail to intervene. They may scroll past the hurtful comments, share the post without taking any steps to stop the bullying, or simply remain silent. One reason for this is the sense of anonymity that the internet provides. Online users may feel that they are not directly accountable for their inaction since their identities are hidden behind usernames and avatars.

Another factor is the diffusion of responsibility. With thousands or even millions of potential viewers, each person may think that someone else will step in to report the abuse or offer support to the victim. Additionally, the fast – paced nature of the digital world means that content is constantly being refreshed, and bystanders may quickly move on to the next thing, rather than taking the time to address the harmful situation.

The impact of this digital bystander effect can be devastating. Victims of cyberbullying often suffer from severe emotional distress, depression, and in extreme cases, may even consider self – harm. The lack of intervention from online bystanders can embolden the bullies and make the situation worse. It also sends a message to the victim that they are alone and that no one cares about their well – being.

Fact 10: Overcoming the Bystander Effect

Despite the prevalence and power of the bystander effect, there are several effective strategies that individuals can adopt to overcome it. Awareness is the first step. By understanding the psychological mechanisms behind the bystander effect, such as the diffusion of responsibility, social influence, and pluralistic ignorance, people can be more conscious of their own behavior in emergency situations.

When faced with an emergency, it’s crucial to break the cycle of inaction. One way to do this is to take personal responsibility. Instead of assuming that someone else will act, remind yourself that you are capable of making a difference. For example, if you witness a person in need of help, make a conscious decision to be the one to step forward, whether it’s calling the authorities, offering first aid, or simply providing emotional support.

In group settings, it can be helpful to assign specific tasks to individuals. If there are multiple bystanders present, you can say something like, “You, call the ambulance. And you, stay with the person until help arrives.” This clarifies responsibilities and reduces the diffusion of responsibility among the group.

Educating the public about the bystander effect can also have a significant impact. Schools, workplaces, and communities can organize awareness campaigns and training programs to teach people about the importance of intervening in emergencies and how to recognize the signs of distress. By promoting a culture of helping, we can encourage more people to take action when others are in need.

In conclusion, the bystander effect is a complex and concerning phenomenon that can have tragic consequences. However, by understanding its underlying causes and taking proactive steps to overcome it, we can all play a role in creating a more compassionate and supportive society. Remember, in an emergency, your actions could be the difference between life and death. So, don’t be a bystander. Be a hero.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the 10 facts about the bystander effect we’ve explored paint a vivid and concerning picture of human behavior in emergency situations. From the tragic Kitty Genovese case that first brought this phenomenon to light, to the complex psychological mechanisms like the diffusion of responsibility, social influence, and pluralistic ignorance that drive it, we see how easily individuals can be swayed into inaction.

The impact of group size, the fear of evaluation, the ambiguity of the situation, cultural differences, and the new challenges posed by the digital age all contribute to the staggering statistic that 90% of people may fail to act. However, there is hope. By being aware of these factors and implementing strategies to overcome the bystander effect, we can change the narrative.

Each of us has the power to be the exception, to be the one who steps forward and makes a difference. Whether it’s in a real – life emergency on the street or in the digital realm of cyberbullying, our actions matter. Let’s strive to create a world where we don’t just stand by, but actively reach out to help those in need. After all, a small act of kindness can have a profound impact and potentially save a life.